“Great things have small beginnings.” David (Michael Fassbender) has no idea what he has at the tip of his finger, but he does know how to find out. As he learned from his favorite movie, “The trick…is not minding it hurts.” The only confusion is about who is supposed to suffer.

I’ve previously written that my favorite film directors often simply want to make the same movie over and over again. To really love their work is to be game for this perfectionist endeavor, to appreciate the refinement and expansion of an old theme, and not to be overly-concerned with eclecticism and novelty in the movie-going experience.

Prometheus–I will try to downplay spoilers–is director Ridley Scott‘s most-developed homage to his own past work. His filmography includes 2 films that re-defined the science fiction genre just 3 years apart (Alien, Blade Runner), a gripping but grueling war film (Black Hawk Down), interesting portrayals of corruption and dysfunction in American law enforcement and intelligence (American Gangster, Body of Lies), and alternately took liberties or speculated about history in order to create mythology relevant to the present (Gladiator, Kingdom of Heaven). And though few directors have had as many visionary triumphs as he has, from time to time his movies have simply been awful (Hannibal).

And one of the things about Prometheus that have intrigued me the most, as its opening weekend draws to a close, is the polarizing effect it has had upon audiences. Though reviews have tended to be positive, and the film was very well-received by critics, there is a deep divergence of opinion between those who loved Prometheus and those who hated it.

I was among those who loved it. I’ll say no more about the basic course of the plot than can be gleaned from the film’s many trailers: Archaeological evidence from many primitive yet comparatively-advanced cultures across the Earth consistently reveals a map of a star cluster in a distant part of the Galaxy–so distant, in fact, that were it not for the almost-impossible coincidence of its depiction in these early societies so temporally and geographically distant from one another, there is still no way they could have observed it with the unaided eye. So, with an optimistic investment of $1 trillion by the Weyland Corporation (still a lot of money, I take it, in 2089), the leaders of that project and a crew of 15 others set-out for the only terrestrial body in that star cluster found to be capable of supporting life. This turns out to be a large moon of a gas giant planet with disappointingly-toxic levels of carbon dioxide and dangerously-abrasive sandstorms on its surface. But the expedition hasn’t traveled that far into space to look for traces of naturally-occurring alien life; they have gone, quite literally, to meet their makers.

Another major plot point can be gathered directly from the trailers: The power to create life from scratch and the power to destroy it seem to be inherently-linked–or at least the Engineers, as they are called, didn’t distinguish between them. “We were so wrong!” 1 of our protagonists laments in a trailer. Indeed, our protagonist has an almost-foolish confidence about her in the providential nature of what she will find. There is an explicit suggestion that her religious faith led her to reach-out trustingly towards what she hypothesized are her creators; in fairness, other characters prove to be prone to blasphemy or even sacrilege, and they exhibit the same self-assurance, bordering on sleepwalking.

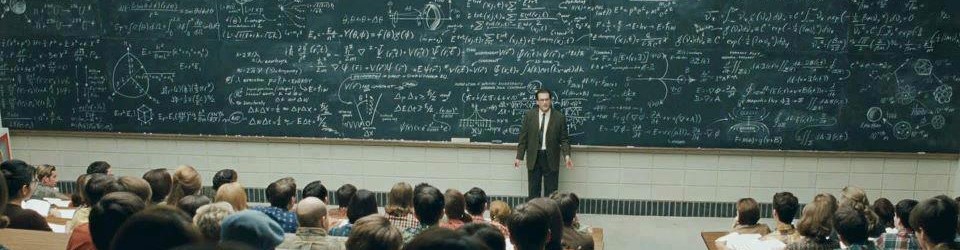

The characters of Prometheus (mostly) have an earnestness to them, but should feel familiar to those familiar with Ridley Scott’s filmography, or with the Alien series. There’s a robot with a murky agenda, a corporate minder, a salty captain, a corporate executive with a deep-seated need to achieve grandiose ambitions, and a complete crew of the sort of gruff oddball specialists you could entice to voyage into deep space with a secret destination and purpose. Then there’s the heroine, somehow less-mysterious than Warrant Officer Ripley in Alien but nonetheless resourceful and resilient–able to act when alone. (This doesn’t change the fact that she is almost stupidly-naive when we meet her, but oh my will she learn.) These characters aren’t just of a familiar type from the Alien series but in some cases from Blade Runner. There are themes that are as familiar (or more-familiar) from some of Scott’s other films: The total immorality of corporate power (Blade Runner), the dangers of self-assurance and the presumption of the routine (Black Hawk Down, American Gangster, Body of Lies), and even stranger common threads such as the erstwhile-living begging for a fiery death (virtually obligatory in the Alien series), a misanthropic verbal reference to parricide (Blade Runner, Gladiator), and the sense of danger and inevitable disappointment in confronting one’s maker (Blade Runner). The richness of self-allegory in Prometheus affords Scott–like other directors including Roman Polanski, Francis Ford Coppola, Terry Gilliam, David Fincher, and Darren Aronofsky–to tell us his favorite story again, but with a different, more-unitary significance from the other times.

Prometheus was written in part by Damon Lindelof, 1/2 of the team of writers that led the groundbreaking TV series LOST through 6 seasons of ambiguities both of context and character to what for many was a frustrating conclusion. I was game for it then, and I’m game for it now. Much like my beloved TV series LOST or the J.J. Abrams-Matt Reeves monster feature Cloverfield, some of Prometheus’ questions are settled by outside material–in this case, a viral video. Peter Weyland, the corporate executive whose goals almost re-define hubris, appears in a 2023 TED talk to ruminate on the wildly-accelerating nature of technological change. Reflection on telescoping technological change dates back at least to the 1600s. But consider the manipulation of nature possible now, then consider what past generations of futurists described as “godlike” power. What we can do now already renders the “past future” as far inferior. It provokes a reaction like vertigo.

“We are just 3 months into year of our lord, 2023,” Weyland goes on, “At this moment in our civilization, we can create cybernetic individuals–who, in just a few short years, will be completely indistinguishable from us.” This means the robot David (portrayed by Michael Fassbender in a performance that may even exceed the iconic pitch he achieved as the emerging villain Magneto in X-Men First Class) hasn’t been created at this time. We can further infer from this that David loves Lawrence of Arabia because he was made that way.

“It must have been horrible to lose Dr. Holloway like that after losing your father under such similar circumstances. What was it, then–ebola?”

“…How do you know that?”

“I watched your dreams.”

Weyland continues: “…Which leads to an obvious conclusion: We are the gods now…” He says it with certainty but a measure a trepidation, and there is grumbling from the audience. However, he goes on to finish his self-introduction to great applause. Weyland masterfully escalates his presentation to this rousing conclusion–and it’s the wrong conclusion. It’s woefully wrong. The central tragedy in Prometheus is essentially the same as that of the corporate executive in Blade Runner: We amass godlike powers to reconstitute nature’s substance yet always remain entirely-human, bound by the limitations and vulnerabilities of that substance itself. Our own rapidly-advancing technology has done nothing to change this fact, so we must face our mortality at the end of a life so much more-brilliant and empowering than what was possible in past centuries. By the climax, we see how plainly this cruel irony of our enduring mortality has consumed Weyland.

He invokes Lawrence of Arabia–as the android crewman will many times–in particular, the early scene in which Lawrence, then wasting-away in Cairo, extinguishes a match flame between his fingers for the entertainment of his military fellows. The movie opens with the same. “You’ll do that 1 time too many. You’re only flesh-and-blood!” 1 man exclaims.

Lawrence brushes this warning off with mirth. But that warning is even more the story of Peter Weyland than it is of Colonel Lawrence. It’s equally the story of the Engineers who our protagonist went to space to find. They are able to manufacture life of astonishing complexity from its base components in mere hours of percolation. The explorers of this windswept moon discover in short order that this race of creators finally created life so prolific, dynamic, and aggressive that they couldn’t make use of what they created. Of course, by then the explorers do make contact–but not at all with what they expected.

Yes, the light is dazzling. But it will go out. And then there will only be what the Enginneers left in that place when they abandoned it or died, thousands of years ago.

I would be remiss as a Liberal Ironist if I passed up a good opportunity to remind people that cruelty is the worst thing we do. There is a lot of cruelty on display in this film, some of it petty and surplus, some of it monstrous and purposive. In a filmed correspondence to the crew of the Prometheus, Weyland calls David “the closest thing I will ever have to a son,” but says David, being an android, doesn’t have “a soul.” (At that moment the look on David’s face says to me that he’s lost–a very-soulful state.) David has to deal with quite a lot of disavowal of his humanity, merely because he is a synthetic person. Most of this torment comes from 1 of the researchers, who almost experiences despair when his hopes of meeting an Engineer are dashed, but when asked by David why humans created him, says tauntingly “Because we could.” Out of all of them, only David is unfazed by the possibility that the Engineers have no compassion for humanity, that they may have created us “because they could,” that they may see in us only lab rats expropriating prime real estate. There is a suggestion here that the capacity to create and shape life is followed close by the temptation to see life–even sapient life–as a malleable object rather than having an inherent worth and dignity. The Engineers’ talents–as far as we are allowed to see–emphasize conversion of previously-meek organisms into extremely-resilient predators. (Director Scott personally offered the theory that this technology was intended for military purposes.) In the end they produced something volatile beyond their own reckoning and means of control. As Christopher Nolan put into the mouth of Nikola Tesla in The Prestige, “You are familiar with the saying, ‘Man’s reach exceeds his grasp?’ This is wrong. Man’s grasp exceeds his knowledge.” As our powers become more-godlike, so do the moral and practical hazards become more-fraught, of confusing ourselves with gods. We see not the cruelty we do, and we cannot foresee the injury we bring to ourselves. We remain very human.