“…I cannot tell you exactly how much time passed or how much happiness there was, but then he threw her away. He had no other children. His wife had no children. So, he kept the child and threw her away. You know, a man could do that in those days. They had the power and the freedom…”

That line, given by a local historian who runs a bookstore, has a sort of personal irony for me now: Having seen Vertigo at least 4 times before this Saturday, I hadn’t read the inherent dramatic irony in it–that in this movie there are 2 men who have the power and the freedom to treat the women in their lives horribly. Alfred Hitchcock always seems to like the idea that “nothing has changed.” There are really only 4 characters in Vertigo–2 men and 2 women. The women are in the story so the men can make them suffer; the men are in the story so they can make the women suffer, and do so because they’re suffering already.

Having long-since acknowledged the obviously-“uncivilized” nature of John “Scotty” Ferguson’s fetishistic attachment to a lost lover’s image, this grim joke–the message that nothing has changed and that the men who are inclined to take whatever they want still seek “the power and the freedom” to do it–somehow completely changed my perception of the film this time, as though just below their well-dressed and soft-spoken comportment, Scotty and his college acquaintance Gavin Elster are savage beings of a very old type, not just beyond the influence of moral convention but apparently unable even to see the fruitlessness of their own passions.

Having long-since acknowledged the obviously-“uncivilized” nature of John “Scotty” Ferguson’s fetishistic attachment to a lost lover’s image, this grim joke–the message that nothing has changed and that the men who are inclined to take whatever they want still seek “the power and the freedom” to do it–somehow completely changed my perception of the film this time, as though just below their well-dressed and soft-spoken comportment, Scotty and his college acquaintance Gavin Elster are savage beings of a very old type, not just beyond the influence of moral convention but apparently unable even to see the fruitlessness of their own passions.

Gavin Elster is unhappy that the San Francisco he knows is changing...and that his wife is possessed. (One of those causes of his unhappiness is even real.) Note the extreme distance between foreground and background in this perspective: I'll come back to this again. And again.

Throughout his work--centrally in Spellbound, Vertigo, Psycho, Marnie and Frenzy, Hitchcock had a longstanding interest in both narrative and symbolic representation of the unconscious drives in human beings.

The Liberal Ironist was beginning to reflect on this upon leaving the theater last night, when to his surprise he found that while he had been inside it had been overrun with a monstrous horde of the walking dead. Their expressionless faces, sagging arms and dull eyes still trouble me as I write this. However, they were slow zombies–in most situations little more than a nuisance so long as you don’t do anything stupid. In a matter of minutes I was several blocks away, the lumbering, mindless creatures had not followed me, and I was able to reflect on the film again.

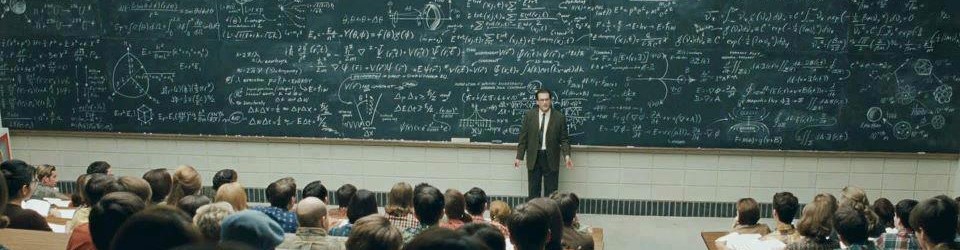

Hitchcock is the first director to give me a sense of vertigo from ground-level--though it helps when someone actually falls. Hitchcock pioneered 2 visual techniques that transformed the way I watch movies (and which is intended to be more broadly-subversive). In one part, background elements, including people, pass from a mundane, even restful order to do something shocking. In the other, rarer form, something awful is concealed from view by an inert, innocuous object. Either technique provokes mistrust of the received appearance.

As I was saying, this is at least the 5th time I have seen Vertigo. It becomes a little more-troubling every time I see it. From his brief engagement in college to his friend Midge and his continuing bachelor status, one might already have concluded that there is something a little “off” about Scotty; in truth he is destined to be alone. There is no indication that he (or she) has had any romantic attachments since that time; there are mild insinuations to the contrary. By contrast, Roger Thornhill, the protagonist of Hitchcock’s frequently-comedic North by Northwest, at one point asserts “I have two ex-wives, a mother and several bartenders depending on me.” In Hitchcock films, there are protagonists who have and protagonists who haven’t managed to consummate their love; in the latter case (as in the recent, comparatively-faithful remake of All the King’s Men), this detail of characterization has a way of taking control of the entire plot, literally violently hijacking the movie–as in Vertigo and also Psycho, 2 years later.

"Somewhere in here I was born...and there I died. It was only a moment to you, you took no notice." Much like with his simultaneous narrative and symbolic portrayal of our fundamentally irrational motivations, Hitchcock likes to punish our lack of attention with both word and image. I'm hard-pressed to think of another director who does this so consistently.

If we can take his actions throughout the film as any indication (and they are certainly more-emphatic than his words) Scotty’s lonesomeness isn’t a mystery. Upon discovering his object of desire, he begins to gratify his desires without hesitation or reflection, even insisting in speech that he will “take care of” the object of desire; for the most part he takes control of her. Having rescued Madeleine Elster from drowning, Scotty not only brings her back to his apartment, but immediately and actively sets about arranging all aspects of this scene to match some fantasy image.

The Marxist movie critic Slavoj Žižek (considering the breadth of his writing this is as good a title to give him as any), writing in The Fragile Absolute, digressed on a debate as to whether Scotty’s climactic loss of his object of desire means his liberation from a burdensome and unethical pathology or his universe’s loss of its minimal consistency. On every previous viewing I’d suspected the climax to be a disaster from which Scotty’s mind couldn’t possibly recover; but this time I noticed the quiet certitude of his words, “No, no, it’s too late, she’s gone–She’s never coming back.” Having found that the object of his desire was in fact real–and immanent!–he despaired. Again there is a powerful irony to this: He found the woman he was looking for, and she really loved him. Was he really so indignant at the thought of an elaborate deception, having always been so coercive himself?

There is a simple explanation both for his climactic resignation and his continuing lack of interest in his friend Midge, and it’s the closest thing the Liberal Ironist can find to a “key” to Scotty’s character: His object of desire had to be weaker than him, stupider than him. She wasn’t: She was real.

Both the story and the storytelling are marvelous in Vertigo, and here we get an early, trend-setting example of a twist. Upon seeing it a second time you can find yourself watching a completely-different movie: Once voyeuristic from the perspective of a man, then voyeuristic from the perspective of a woman. Note once more the sense of vertigo evoked from ground perspective. I'm telling you, it's everywhere.