The gathering storm in Syria powerfully demonstrates the limitations of violent spectacle as a means of securing the future, as the most thoroughly-cowed country in the Middle East trembles with the pro-democracy convulsions that have shaken almost every Arab state.

How can I call Syria “the most thoroughly-cowed country in the Middle East”? It’s true that I have previously described Tunisia as “the poster child for durable autocracy” and described Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi as “an impossible monster,” but the single biggest act of destruction in the post-colonial Middle East happened in Syria over 3 weeks of February 1982. It happened in Hama, a city in the north of the country–and compared to the protests, terrorism and war seen other parts of the Middle East this episode made Syria as quiet as a tomb for 29 years. Those 29 years of silence came to an end on Friday, February 18th–6 days after Hosni Mubarak abdicated the near-monarchy that was the Egyptian presidency. Though it was quickly overshadowed by the already rapidly-escalating violence in Libya, on that day in Syria 1,500 protesters took to the streets in protest of corruption and repression in Syria. The Guardian reported that this protest was explicitly anti-police–a response to a police beating of a local businessman–and included chants of “With our soul, with our blood, we sacrifice for you Bashar.” Bashar al-Assad is Syria’s reigning President-for-life, the region’s sole example of a nominal president who inherited his position from his father, Hafez al-Assad. Hafez al-Assad is the man who is responsible for Syria’s surface calm, though he accomplished as much through as much ruthlessness as circumstances required.

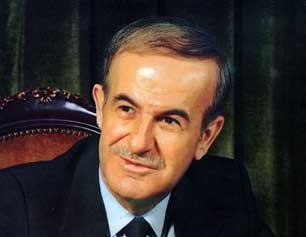

Hafez al-Assad was almost always pictured smiling, but considering the political forces he contended with--and what he did to them--his vision of the world must have been dark indeed.

There are many pictures of Hafez al-Assad out there; in almost all of those publicly-available, he is smiling. This is noteworthy because of the dark forces he contended–and often made pact with–as first a ruling party man and then as dictator of Syria. Hafez al-Assad came to power in the Ba’athist coup, but in 1970 he took control of the party and the country during a time of political chaos. He moderated the party’s at times unwieldy socioeconomic radicalism, but much as Saddam Hussein in Iraq, the Khalifa monarchy in Bahrain, and Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi in Libya, Assad found himself in control of a state that distributed benefits through a structure of tribal patronage. In this country as in others, this manifested as a form of preference by religious sect.

If anything sectarian differences are more-complicated in Syria than in most Arab countries. There are religious sects in Syria’s cultural makeup (and network of authoritarian patronage) that scarcely exist elsewhere in the Middle East. The State Department’s 2010 Report on International Religious Freedom finds that Syria’s population of about 21 million is about 74% Sunni Muslim, that being the conventional, decentralized version of Islam that the vast majority of Muslims in the World adhere to. Just over 1/8 of Syrians are Shi’a (the hierarchical and scholastic next-largest sect, with majorities in Iran, Iraq and Bahrain), Ismaili or Alawite. About 10% of Syrians are Orthodox Christians, and about 3% of Syrians are Druze, members of an extremely-secretive but small and benign religion that developed out of Islam but doesn’t accept converts. Much as was the case for Shi’a Arabs and Kurds in Saddam Hussein’s Iraq (60% and 20% of Iraq’s population, respectively, compared with Sunni Arabs’ 1/8), the vast-majority Sunni Arabs are losers in Syria’s patronage system because a dictatorship with an insecure economy must dole-out benefits on a reverse-pyramid scale to maintain elite fidelity while conserving limited resources. At the top of this caste system of government patronage are Syria’s Alawites, the sect of which the Assad family is a part.

The Alawites are supposedly a sect related to the Shi’a, but a common opinion among many Muslims regards them as outright heretics. With a belief system many Muslims consider bizarre and its small minority population visible in many uncontested positions of power and wealth in a country that has never been democratic, Syria’s Alawites likely have a siege mentality about them. This fact itself may have been a catalyst of the Hama Massacre of February 1982, in which the Assad regime committed an abrupt political mass murder to break the power of the Muslim Brotherhood in the country.

This should help give perspective on how long Egyptians lived with President Hosni Mubarak: Here Syrian President Hafez al-Assad (left) says goodbye to him as he leaves the Syrian coastal resort town of Latakia in summer 1993. Photo courtesy of SANA/AFP/Getty Images.

Between 1978 and 1982 a much more-militant Muslim Brotherhood than the one participating in Egyptian politics today had carried out a campaign of guerilla attacks, assassinations and terrorism across Syria; in 1981 the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood assassinated Egyptian President Anwar Sadat for making peace with Israel; the perpetrators of this terrorist act cried “We have killed Pharaoh!” before being killed by the Egyptian Army. (Having survived the assassination, Sadat’s Vice President, Hosni Mubarak, soon became President and imposed a state of emergency; we now know how that turned out.) On June 26, 1980 the Muslim Brotherhood made a similar attempt to assassinate Hafez al-Assad; he had to dodge machine gun fire, kick a grenade, and rely upon the valor of one of his bodyguards, but Assad survived. His brutal brother Rifaat immediately ordered the executions of hundreds of jailed members of the Brotherhood in retaliation for this attack.

What happened in Hama was the result of a succession of events even more unanticipated and extraordinary than Hafez al-Assad’s survival of the Brotherhood’s assassination attempt. A Syrian Army unit’s early-morning random encounter of a man known as Abu Bakr, the commander of the Brotherhood in Hama, led to an ambush of that unit, which led to its call for reinforcements and siege of Abu Bakr, which led to the latter’s call for a general uprising in Hama. This desperate gamble for resurrection resulted in the Brotherhood’s seizure of the city, politicide of Ba’ath Party officials there, and declaration of an Islamic republic before the Sun was up. The date was February 3, 1982.

The Hama Massacre deserves its own post and discussion; for now suffice to say that between the Sunni Islamists and the Sunni landed class that opposed his radical economic policies, Assad didn’t have any political allies left in Hama following the Brotherhood’s politicide of Ba’ath Party officials there. By the end of the month Hama was essentially destroyed, as at least 30,000 civilians were killed and many more sought refuge elsewhere in the country; 100,000 Hama residents were expelled from the country. Again, Hafez’s cruel brother Rifaat was the tactician behind this simultaneous act of suppression, revenge, and terror. Not just the Muslim Brotherhood’s insurgency but all civil society and popular expressions of political opinion were broken after these events. A friend of mine who studies Middle Eastern politics told me after a long visit to Syria that its people are the most-thoroughly atomized and fatalistic he has ever seen. In public discussions in Syria it is apparently known as “the Incident;” the rest of the World simply calls it the Hama Massacre.

Though Hafez continued to rely upon his secret police, the Mukhabarat, for spying, torture and both official and extrajudicial killings, Syria was much quieter after the bloodshed at Hama. Syrian dissidents of all ideological and tactical persuasions realized that revolt didn’t just mean a risk to their own lives–a wager revolutionaries often assume they are making–but the possibility that their home would be destroyed. When Hafez al-Assad died an old man in June 2000, he essentially bequeathed leadership of the Ba’ath Party and Syria to his son Bashar, a dentist-by-training, following a succession of events reminiscent of The Godfather.

Bashar al-Assad wasn't meant to be President-for-life. His brother had been groomed to succeed their father in government, and Bashar went to London to study dentistry. But his medical career was cut short when his brother died in a car accident in 1994, and Hafez al-Assad immediately began years of military and political training for his new heir. Associated Press photo.

The writing on the billboard reads "God protects Syria." The mixture of religion and patriotism is oddly-reminiscent of a certain American political expression; of course, the government-sponsored billboards adorned with the leader's image are anathema to American political culture. Photo courtesy of Bertil Videt.

It’s funny to look back now and think that Syrian President Bashar al-Assad didn’t have any visible political ambitions before circumstances led his father to decide upon him as the heir to the Assad Regime. The Liberal Ironist thinks this is funny because President Assad’s recent, very illiberal comments suggest, as has been the case in many Arab States, that he has no intention of listening to the thousands of protesters amassing in his streets. This is all the more remarkable because, much as with Emir Hamad Isa bin al-Khalifa of Bahrain, the protesters initially weren’t calling for his removal at all but rather an end to corruption and emergency rule, and liberalization of the Syrian parliament.

President Assad’s response hasn’t been very encouraging–for those of his people whom have taken pains to demonstrate their loyalty to him even while stating their grievances of for his own long-term prospects. Last Wednesday, the New York Times reported, Bashar gave a speech in which he was expected to make political concessions but in which he made a muted imitation of the delusional Colonel Muammar al-Gaddafi of Libya or the very shrewd but shameless President-for-life Ali Abdullah Saleh of Yemen. In short, he used the bully pulpit to claim that Syria had fallen victim to a foreign plot, and that protesters–against the police and against corruption, and for democracy–were either dupes of foreign powers or conspiring traitors.

The Assad Regime has been more-or-less opposed to United States foreign policy since Egyptian President Anwar Sadat made peace with Israel under the Camp David Accords in 1978. While its hostility towards Israel, sponsorship of Hezbollah and protection of Hamas' military leadership, alliance with Iran and failed pursuit of nuclear weapons make Syria look like an ideological belligerent on the order of Saddam Hussein's Iraq or Colonel Gaddafi's Libya, the Assad Regime is best thought of as a consummate opportunist. Failing to keep political pace as many of its neighbors made peace with Israel and developed working relations with the United States, having economic incentives to continue meddling in Lebanese politics, and facing a newly-confrontational United States following the September 11th terrorist attacks, Bashar al-Assad found a powerful revisionist ally in Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, elected in 2005. Photo courtesy of Slate magazine.

It could be Bashar is doing this out of some understanding of duty; the Liberal Ironist wouldn’t put it past him. He might be thinking that his family–indeed, his very tribe and other tribes allied to the regime–depend upon the patronage the state can give them. He may have thought long and hard about the fate of other resented minority groups in former European colonies and resolved to protect his community. He may have looked at Somalia, Iraq, Libya and Yemen and concluded that his sure hand is infinitely preferable to an imagined anarchy. It may be that Bashar wants to be the ruler his father was training him to be. His mild demeanor suggests he does not believe, as Muammar al-Gaddafi or Saddam Hussein’s sons clearly believed, that he is simply superior to other people. But whatever his motives are, Bashar al-Assad has shed his reformers’ image and done what most Arab autocrats have done in the face of this unprecedented uprising: He has blamed the victim and sought to preemptively justify worse violence to come.

Things could just quiet down. The Liberal Ironist doesn’t believe that democracy is about to sweep through most of the Middle East (though there was a 2-week period between the fall of Ben Ali in Tunisia and the first very-bad weekend of violence in Egypt where he didn’t expect revolution in Egypt either). The uprising by the majority Shi’a in small Bahrain may be effectively quelled by an army deployment from its larger neighbors. If Yemen truly descends into chaos, that plus an ossifying civil war in Libya could make Bashar’s pretext of maintaining order seem rational, and discourage protests. Maybe enough violence by the Assad regime will simply quell the uprising in Syria. But so far the evidence still suggests mounting anti-regime protests–and Bashar may now have staked his legitimacy with a trusting public in order to side with Syria’s sectarian hierarchy.

What Bashar should have learned from mounting protests in his country is that the most-spectacular act of repression you could think of only buys a ruling regime 29 years; after that, you still have to deal with the people’s aspirations. This is why we have no empirical concept of “successful repression.”

Pingback: Libya’s Mad Dog Dictator Bears His Fangs: Now is the Time for the United States to Get Involved | The Liberal Ironist

Did these two have anything to do with the Boston tragedy?